A common feature in the four climate events for artists and scientists that I helped organise for TippingPoint from 2014 to 2016 — and I think many of their creative conferences over that charity's twelve years — was the introductory small group activity where we would share a 'show and tell' session with a dozen or so people. We'd all been asked to bring a single object, or something to represent it, that held special emotional meaning for us in the context of our gathering, and to talk about that for a few minutes.

In her essay for Future Remains: A Cabinet of Curiosities for the Anthropocene, historian Libby Robin says that ”objects are powerful tools, engaging emotional responses including grief and uncertainty and other negative feelings about change.” These group explorations with TippingPoint were rewarding opportunities to share, to listen, to appreciate the power of small stories when engaging with issues of often daunting scope and scale.

Although each object and its significance were very particular to the teller and to a time, place and, in many cases, people they were recalling, the personal stories we all encountered invariably revealed a wider resonance and a growing sense of shared meanings. Far more than a simple 'ice breaker' preparation for a day or two of immersive encounters with climate and nature predicaments, this simple space for storytelling created a sort of ‘memory space’ in which our explorations could take root. I think it was the concrete specificity, the felt reality of the objects we discovered in each other’s company that helped us to ground a collective knowledge and creativity.

There is always plenty of scope for the weight and the tone of our planetary crises to overwhelm us or for the issues to spiral away into abstractions. Objects can help to place us, both in the immediate here-and-now of sharing them, but also in the where-and-when-and-who that the objects bring with them. Objects are always objects of the imagination as well as of the physical world.

Anthropocene collections

It was my TippingPoint experiences that prompted me to launch our ClimateCultures online project, A History of the Anthropocene in 50 Objects. It could have been any number, of course, and the idea of 'a history' (singular) was pretty malleable. I invited our members to bring objects — either real or imaginary — that resonate for them when thinking about the past, present and possible futures in this age of our species’ presence as a geological force. That, naturally, meant discussing three objects each rather than just the one.

And for the past four years, ClimateCultures has also been home to an online Museum of the Anthropocene, curated by Dr Martin Mahony, a geographer at the University of East Anglia who devised and teaches a third-year undergraduate class, Human Geography in the Anthropocene. We've just added Martin’s selection of six mini-essays from his latest cohort of students, bringing our collection to 24 entries so far.

The annual Museum is built collaboratively as a pop-up exhibition at UEA, with each student selecting something they think is particularly eloquent of the historical, political and cultural processes that have led us into the Anthropocene, or which helps us imagine a world beyond it. Their texts reflect debates on when this new age began, what our choices either reveal or conceal about how it is made and perpetuated, and how it impacts on different people, on other beings and on the planet we share.

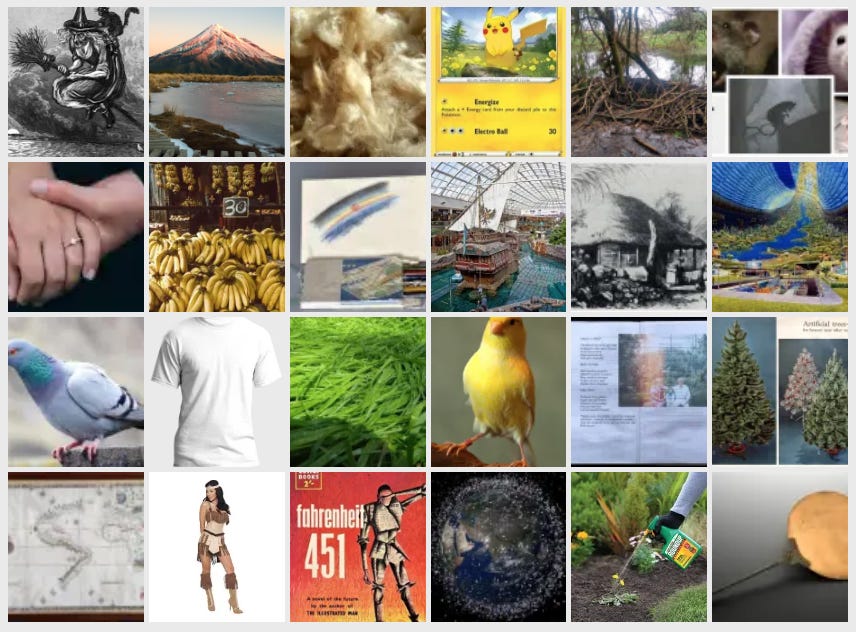

In the Museum, you will find thoughtful, informed short pieces on

Bananas

Beavers

Canary birds

Christmas trees

Cotton-based t-shirts

Diamond engagement rings

Fahrenheit 451, the novel

“Indian Squaw Pocahontas Costume Ladies Fancy Dress Sexy”

Lawns

Mirrors

‘Orbital sunrise’ sketch, Alexei Leonov

Pigeons

Plantation gardens

Pokemon

Rats

Roundup, the glyphosate-based herbicide

The 'Salviati planoshere' world map, 1525

'Santa Maria' at the mall

Space junk

Sweetgrass

Taranaki Maunga

Witches

Wool

Zapotec poetryAnd fourteen ClimateCultures members — artists, curators, poets, science historians, social scientists, writers & more — have now used our series History of the Anthropocene in … 42 Objects (so far) as a space to cast their imaginations backwards, forwards and maybe sideways through millennia and the present moment.

Each post is in some way a dialogue between the contributor’s three objects, intended to be read as a textual triptych. But I think there is a wider set of conversations to be heard across our growing ‘cabinet of curiosities’. If so, maybe separating and reordering them here can be a tentative first step in that direction. Looking across our 14 posts to date, you will encounter

13th-century image of Cosmic Man

19th-century book on clouds

3D collage of disparate elements

25,000-year-old stone ‘Venus’ figure

Acorn

Atmospheric experiment destined for Mars

Bag

Bronze bell

Chalk hillside figure of a human, age unknown

Child’s bone kayak from the Arctic Circle

Classic tractor

Coal

Coffee bean

Field of darkly reflective solar panels

First blanket

First long-lasting record stylus

First new theatre production to be illuminated entirely with electric lights

Floating metal island

Fragment of brown slipware pottery

Fragment of oak from the seabed

Homemade wooden paddle

Incandescent lightbulb

Metal and paper currencies

Micro battery

Mobile phone

Moss-covered bleached piece of coral

Outdoors cooking set

Photographic series documenting artistic interventions on an iceberg

Plaque marking the birthplace of the world’s first plastic

Prayer wheel for generating power

Record taking sounds of Earth to the stars

Satellite network observing Earth

Sculpture of a calcified bladder stone

Search engines

Shell sculpture on an eroding coastline

Spillage of bitumen

Stone from a loch beach holiday

Sugar sculpture of a bleaching coral reef

Sundial

Urban fatberg rehoused in a museum

Used water bottle

Wayang kulit leather puppetConnecting with the disconnect

As Martin says in Anthropocene Naturecultures: Where are the Boundaries?, his new post for ClimateCultures:

“We can read the history of the Anthropocene as being a process of drawing boundaries and severing connections — of declaring ‘nature’ to be fundamentally separate from humanity and human culture, and thereby positioning it not as a bundle of relations which holds and sustains us all, but as a pool of resources to be exploited and put to work.

“Does the heralding of the ‘Anthropocene’ represent the final triumph of such boundary-making and hierarchy-constructing? Or does it represent the end of the illusion of such boundaries? That’s not just a philosophical question, but arguably also the crux of the collective choices ‘we’ need to make to steer a course through the Anthropocene.”

Some of the objects and entities across both our museum and our history series evoke a sense of deep time, whether on human or planetary timescales, connecting us with ancient societies or natures that still exert either a cultural force or a personal imaginative pull today. Others express spatial or societal scales that, while emphasising the impact of our choices and actions, decentre our Ozymandian experiments in civilisation within the vast cosmological histories in which they are embedded. Many address our intimate concerns - food, shelter, community.

Viewed as cabinets of curiosities, through their juxtaposition of objects from student geographers and from artists, researchers and curators with diverse interests, these two projects offer in Libby Robin’s words, “a tool to explore the Great Acceleration of change at the apocalyptic turn of the millennium. … a way to unpack the curious in strange times … to play with curiosity itself.”

Curiosity, and connection. For me, our two collections convey a sense of connection even as they highlight the pathways to now and our increasing, global disconnectedness from the more-than-human of which we are a part. Together, and with the conversations they can spark between us, they serve as vehicles for our imagination to travel, to reconnect, to navigate futures we can help to bring into being. More hopeful futures, where we realise that a disconnect with the rest of nature is neither inevitable nor irreversible.

As well as Martin’s new post, Anthropocene Naturecultures: Where are the Boundaries?, you can find his introductions to previous iterations of the Museum of the Anthropocene: Objects, Ownership and the Politics of the Anthropocene; Centrifugal Stories in the Anthropocene; Object-based Learning in the Anthropocene. And all 24 student pieces await you Inside the Museum.

A History of the Anthropocene in 50 Objects contains 42 objects so far, from 14 ClimateCultures members: Nancy Campbell, Nick Drake, Sarah Dry, Ruth Garde, Andrew Howe, Nick Hunt, Jennifer Leach, Julien Masson, Jules Pretty, Veronica Sekules, Kelvin Smith, Philip Webb Gregg, Yky, & me.

There is also The Mirrored Ones, my review of Future Remains: A Cabinet of Curiosities for the Anthropocene (edited by Gregg Mitman, Marco Armiero & Robert S. Emmett: The University of Chicago Press, 2018).

And there is a wealth of further creative responses across our blog archive from 2017 to right now, as well as our Creative Showcase and Longer feature and series such as our Quarantine Connection and Environmental Keywords.

This Substack post is part of our series Starting a creative enquiry with climate & nature here on ClimateCultures & more.