Inspired by our latest ClimateCultures post - We are Creatures – a Story of Mayhem with Masks, artist and writer Nicky Saunter’s account of her recent photographic exhibition - I’ve been looking back at previous photographic offerings in our archive.

Through a powerful photographic project drawing on a wildlife street protest she was part of, Nicky created black-and-white images “imagining what might happen at night in a town as creatures show their faces in our human spaces. They are strong, confident and do not seem frightened of us. Have they come to take over? Or are they our almost forgotten selves walking the streets as we lie sleeping in our beds?”

There’s a strong tradition, of course, of using photography to document the ‘real’, whether that’s the beauty and power of nature or a reality degraded by decades, centuries, of human exploitation and disregard. In The Visuality of the Flint Water Crisis, her essay for the ClimateCultures Longer feature, Jemma Jacobs looks at the work of photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier, who captured the strength and endurance of a struggling, marginalised community. In her introductory blog post, Seeing the Flint Water Crisis, Jemma writes how she views “Frazier’s photographs as making visible the invisible. The community of Flint were ignored, their health left to decline as those in power denied the state of their water system. … Her use of the ‘deadpan’ aesthetic arouses curiosity and emphasises the normalcy of racial discrimination. In her documentary photographic style, Frazier provides an intimate insight into the crisis — an understanding that photojournalism within the media is unable to fully render.”

Such direct truth-telling is powerful and needed. But what Nicky’s recent post prompted me to consider was the role of imagination and emotional response within photographic encounters that offer playful yet challenging representations of ourselves. This feels as vital, in a different way, as scrutinising the dominance of power structures and institutions, real and present though that is. Here, we — imagined as ‘animal others’ imagined as ourselves — are in the frame. What we do to the more-than-human, we do to us too, even as we imagine ourselves as somehow separate from nature.

This artistic representation, a form of visual fiction, perhaps sits somewhere between — or better, alongside — the scrutiny of documentary representation and the psychological resonances of abstract photography. All have a part to play.

Visual fictions for bringing experts and citizens together

In Urban Resilience? Art, the Missing Link, Yky argues for a joint commitment between artists, experts and citizens — and what he terms a “cognitive apprenticeship” — to improve a shared understanding of urban resilience. This ambiguous concept is hard to translate into coherent action across the complex of threats and challenges we face under entangled climate, nature and social crises.

“Fictional narratives,” he suggests, “help to transform our own representation of reality. Representing the reality of the world becomes a virtual act and the reality of this virtuality plays a fundamental role in the sense we give to our actions. Fictional narratives are therefore a powerful way to build the required tripartite relationship ‘virtuality-reality-action’ between artists, experts and citizens.”

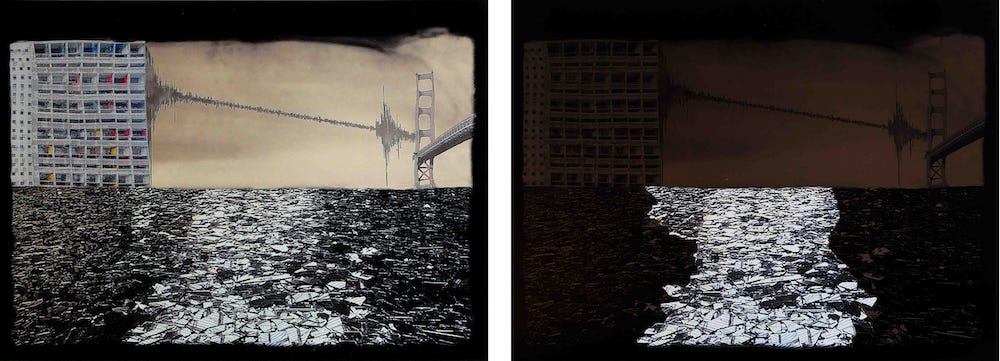

Yky’s form of visual fictions takes the form of photographic diptychs such as ‘Shakes’, which present scenarios of, in this case, seismic destruction. “With architectural symbols, broken reflections, and linear designs that at once feel as much like an earthquake monitor as they do a heart monitor, it talks about an irrational fear: the destruction of our matrix.”

He offers such diptychs as “a ‘theatrical scenette’ with a teaching process,” emphasising that natural hazards play out in sociological relationships, that resilence and vulnerability are related and how our collective responses to disaster can either choose to bounce back to ‘business as usual’ or, more imaginatively, to ‘bounce forward’ to something better.

“In ‘Shakes’ as in my other works, my photographic technique makes use of a well-known property of argentic paper, which is to darken when exposed to light. This will produce a diptych of two images. The first one illustrates the hazard (here, the earthquake) while the second one darkens in time. The comparison between both images will highlight the related disaster and the questioning which will be used to support the pedagogic work with the expert. By doing so, my works contribute to engaging citizens in considering the most appropriate way to operationalize resilience.”

Evoking echoes and undercurrents

For Beneath What Is Visible, A Vast Shadow, Oliver Raymond-Barker makes use of an innovative take on the ‘camera obscura’. During a residency in Scotland’s Rosneath peninsula, he explored the landscape with his own ‘backpack obscura’ invention, a transportable light-tight tent that served as both image-making camera — 70mm lens and mirror extended outside to project an image of the surroundings onto a white groundsheet — and his shelter from the elements. Taken together, his ethereal and unsettling images surface something of the visible and invisible networks and complex histories in a place that is home both to the UK’s Trident submarine nuclear deterrent and the encamped peace activists resisting that presence.

Oliver’s post includes extracts of guest texts he used alongside his images in his book, Trinity: an essay by photography curator Martin Barnes, and a creative memoir from writer Nick Hunt recalling his own time at the peace camp.

“After two extended stays on the peninsula I felt I had enough material to begin the editing process. However, I soon realised that conveying the depth and breadth of what I had experienced was going to be difficult using image alone. The idea of creating a publication seemed the perfect solution as a means of expanding and extending upon my work. I feel the combination of critical and creative texts really help to locate the imagery whilst also providing a platform from which the reader can access the project.”

As Barnes says of Oliver’s work, “the charge of his pictures lingers like a half-remembered dream. … We may intuit from the uncanny appearance of these photographs that the location they depict is a landscape full of echoes; that it holds a deep history resounding with the ominous undercurrents of the present.”

And Hunt’s text brings directly into our imagination the spectral presence of the mobile machinery of unthinkable violence this peninsula’s waters contain, convey, conceal: “It rises up from deep below. Its shoulder breaks the surface. Water thunders from its flank. The daylight makes it gleam. For long months it has been submerged in darkness and in secrecy, nursing its destructiveness. It has seen the bottom of the world, the undersides of ice floes. … It registers nothing of these things. Nothing penetrates. Its mind, if it has a mind, is as blank as a stone. It has almost reached its home. Its velocity starts to slow.”

Meditations in monochrome

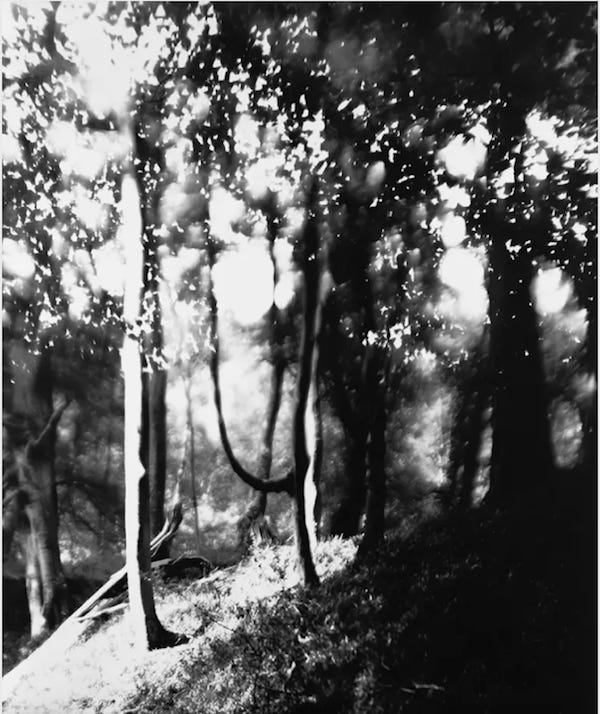

In Black Haiku: Poems for Dark Times, Robynne Limoges takes inspiration from the haiku poetic form — “a minimal poetic form that does not rhyme. It does not always comfort. It does not conclude.”

Her enigmatic monochrome images reward repeated viewings and invite meditation. The eye lingers on the half dozen examples in our gallery — Dialogue, The Wave, Constellation Haiku, The Way of Water, Bird in Flight, The Light is Impenetrable.

“When I began the series I had been photographing nature only sporadically, but my increasing unease in the world led me to choose the natural world for tutoring. I tried to keep foremost in my mind the question of how I might distill the natural world’s organic profusion into minimal yet emotional imagery. Ultimately, I was looking for a means of relief from the constant grappling of humans against nature, an antidote to the high barometer of conflict, a specific visual approach that would suggest, not shout, that might lend a degree of quietude and a point of contemplation, a sotto voce conversation between ourselves and our world.”

Emotional reconnection in nature relationships

For Art Photography — Emotional Response to Global Crisis, Veronica Worrall shares her experience of turning to her garden and capturing its beauty in response to the early lockdown restrictions of the Covid-19 pandemic. For her, both garden and photography were a refuge, as were the Suffolk skies above her, for now emptied of air traffic.

Veronica writes that “I was taking refuge in the blossom against perfect blue. I became mesmerised by the delicate beauty. I was not the only one. Facebook, Twitter and Instagram evidenced a burgeoning re-connection between people and the natural world. How could this be sustained? How could we stay reconnected?” And this prompted her to partner with the natural processes within her garden, co-creating art from her photographic prints, images that express her joy and fear.

“My photographs of blue skies and blossom were returned to the trees and left for months … Nature’s elements and creatures traced over my images. Whilst monitoring my images attached to the trees a few months later, I noticed the skies overhead were becoming crisscrossed with vapour trails as lockdown relaxed. The sky was symbolising my concern that lessons were not being learnt in a rush to return to unsustainable travel and consumer trading.”

The experiment rendered her prints “significantly degraded” as gales washed in but, for Veronica, this co-authoring of the final images meant that “together Nature and I created colourful art pieces, symbolic of the much-needed partnership. We convey the joyful reconnection many had found in our gardens, parks and wayside walks.”

Oscillating between representation and abstraction

Joan Sullivan’s post ‘If I Were a Tree’: Notes for the Pyrocene demonstrates her use of intentional camera movement as a means of ‘seeing’ climate change in new ways in the face of the great violence being done to the natural world.

Moving from a background in documentary photography of energy transitions, Joan now produces work where “I cede my voice to the non-human beings … with whom we share this magnificent planet. … I could no longer justify using my cameras to document climate change from a human perspective.”

“Throughout that summer [2023, with Canada’s record-breaking wildfires across the country], I was haunted by a recurring question: ‘If I were a tree, what would I feel when the flames arrived?’ The first half of this question became the title of my current installation. I imagined myself rooted to the ground, like a tree. I tried to embody the anxiety of a sentient being unable to flee. Using intentional camera movement (ICM), I moved my body in an agitated manner to imitate the flames fanned by high winds whooshing through the parched forest. The resulting images oscillate between representation and abstraction, underscoring our collective ambivalence to the escalating ecological-climate polycrisis.”

Visitors to Joan’s exhibition of ICM images of fire-consumed trees — printed as nine-foot-long, three-dimensional silk sculptures suspended from the gallery ceiling — were able to wander among this hanging ‘forest on fire’. Touching these burning trees and listening to the forest’s ‘voices’ as imagined through specially composed music, people experiencing this unique art became part of Joan’s question to us all: “Can immersive experiences like this decenter ourselves and create empathy towards nonhuman people upon whom we depend for our own survival?”

Ways of seeing

Through a realist documentary approach, through art that playfully challenges us or through imagery that works with the photographer’s and viewers’ emotional presence and our sense of joy, unease or fear, photography offers rich and varied portals between our imaginations and our world. It can engage a sense that our critical environmental predicaments are not a ‘given’, fixed, written into systems and structures entirely beyond our reach.

Whatever the photographer’s approach or particular focus of concern, the image can shift how we habitually see the world. Images might attempt to represent nature, others and ourselves, or instead to render something of our relationships in abstract terms that tap inner spaces beyond the rational — or to oscillate between these modes. Our ways of seeing are many, and we’re reminded, in Dorothea Lange’s words, that "a camera is a tool for learning how to see without a camera."

Whether as visual fictions, a means of surfacing the unseen, meditative reflections or expressions of emotional understanding, these ways of seeing can help us into a conversation between ourselves and the world. A world that is always at work on and in us.

For other ClimateCultures posts by these photographers and links to their websites, visit their profiles in our directory:

Joan Sullivan - a photographer, writer and farmer who focuses on climate change and whose abstract, phenomenological approach to photography expresses her ecoanxiety and gives voice to the nonhuman.

Nicky Saunter - a practical activist, campaigner, social entrepreneur and artist with a particular focus on communication, between people and between humans and the rest of the natural world.

Oliver Raymond-Barker - an artist using photography in its broadest sense - analogue and digital process, natural materials and camera-less methods of image making - to explore our relationship to nature.

Robynne Limoges - an artist who uses photography in a search for illumination, playing out the metaphysical question of just how little light is required to dispel darkness.

Veronica Worrall - an experimental artist using photography to capture movement, time and natural processes, working with nature and traditional alternative photography in attempts to reduce her artist footprint.

Yky - a citizen artist exploring urban resilience whose photographic works use argentic paper's response to light to highlight the challenges raised by climate hazards in urban spaces.

And there is a wealth of further creative responses across our blog archive from 2017 to right now, as well as our Creative Showcase and Longer feature and series such as our Quarantine Connection and Environmental Keywords.

This post is part of our series Starting a creative enquiry with climate & nature here on ClimateCultures & more.

A wonderful post, Mark! Honoured to be included in such good company. Carry on!

Really pleased you are here, Mark. Honoured. My images are on Blue Sky Media Section.